There have been few historical Christian communities that have had a more significant role in shaping our community’s postures of life and mission than that of St. Patrick and the Celtic Christians. Living as a “sent” people who were committed to rhythms of common life, this band of early Christians embodied missional-monastic community in a context that was anything but conventional.

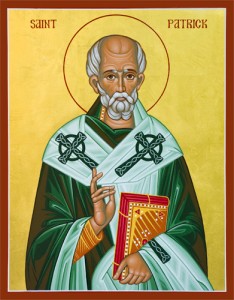

While Saint Patrick of Ireland is one of the most commonly known spiritual fathers of the past 2000 years, he is also one of the most misunderstood. Often associated with green beer, shamrocks and the driving out of snakes, St. Patrick’s life and legacy have been greatly diminished by folklore. Because his legend is so widely spread, there is rich potential for the values of the historical St. Patrick to reach the masses if his story is retold well. Having been raised in Roman nobility and enslaved by Irish barbarians, his role as spiritual father of a hostile population was uniquely shaped by earlier parts of his life. Further, St. Patrick’s ability to create a Christian movement of engagement within a pagan Celtic spirituality offers a rich tradition that, if emulated, has the potential to ignite the hearts and imaginations of Christians around the globe.

After being kidnapped from his home in Briton (Northern England) as a child, Patrick spent six years in slavery tending livestock on the hills of Ireland. During that time he had an encounter with God that would forever change the trajectory of his life and mission. While in the fields, he had a vision of his escape back to Britain and after walking 200 miles through the wilderness, he boarded a ship for Britain. Because Roman roads often didn’t extend to some of the coastal towns in Britain, after his arrival he and his fellow crewmates wandered the large island for 28 days. Nearly starving to death, Patrick prayed for God’s provision and told his captain, “Today he’s going to send food right into your path – plenty to fill your bellies – because his abundance is everywhere” (Freeman, 40).[1] God did provide and Patrick made it home.

The man that returned to his boyhood home was no longer the boy that had been kidnapped six years earlier. Patrick now had a living relationship with the God who wanted not only the hearts of the Romans, but of the Irish barbarians that had enslaved him. Despite being a town hero and his parents begging him never to leave again, Patrick had another vision where he heard a chorus of voices saying, “Come here and walk among us” (Freeman, 50)! Although in much different circumstances than the first, Patrick decided to go back to Ireland.

It was upon St. Patrick’s arrival that the viral movement of Celtic Christian communities took shape and extended throughout the “barbarian” lands. History tells us that Patrick engaged and traveled “to the most remote parts of the island – places at the very edge of the world, places no one had ever been before” (Freeman, 73). St. Patrick didn’t go to Ireland to minister by himself, as the saint knew that the spiritual life and missionary call was not to be lived alone. In fact, the message he was working to share wouldn’t have made practical sense outside of a life lived in community. The Celtic Christianity that was birthed out of Patrick didn’t simply seek the transactional, individual conversion, but it invited others into a life of discipleship and practice. Monastic life set in the context of vocational mission offered a fertile foundation for a movement that was symbolized by journey rather than a static arrival of faith.

Because the spiritual journey is not to be trod alone, communal monasticism grew out of the tradition of Patrick. In a society that was spread thin across the island, monasticism created the first population hubs in Ireland (Cahill, 156).[2] The monastic life in Ireland wasn’t as strict as many other orders in Europe as it promoted movement towards engaging the Celtic culture and the reading of all literature; whether Christian or pagan (Cahill, 159).

It was in these population hubs that the Celtic Christian’s offer us a brilliant model of invitation. Unlike Roman monasteries that were typically built in quiet, remote locations, the Celtic communities were planted right alongside the tribal settlements where the Irish pagans lived and worked. The prevailing opinion in the Roman church was that barbarians were not even capable of becoming Christians. Why? They were considered illiterate, emotional, out of control. But Patrick invited these Irish barbarians into the community to taste and participate in a different way of doing life. He knew that most people need to belong before they believe. They need to be listened to and understood, because when people sense that someone really understands them, they begin to believe that maybe God can understand them too.

These “barbarians” found a home through the invitation of Patrick and this new movement of Jesus followers. And it was only in the context of this invitation that they we able to step towards the invitation of God into a Story that continues to be told through his Community today.

As missional-monastic pioneers we would do well to reflect on the life and mission of St Patrick & consider integrating them into our unique contexts.

Too bad you weren’t with us in Ireland to give us this history lesson when we were on Slemish! 🙂

Thanks for this. Saves me some time in writing things out, so I linked to it from my blog. Great story of a great man and movement.

Glad it was helpful, Scott!

I really enjoyed learning about our brother in Christ, Saint Patrick, I truly did not know the story of his life. Thank you Jon for your love for the lost…and your compassionate vision to help them belong so they one day can believe. Pam C.