Mission is the work of God that the church simply participates in, not the work of the church that we ask God to bless. Jesus commissioned his disciples to join this mission, and the early church sought to faithfully form faith communities that would embody and advance the missio dei. Two major movements in church history have sought to faithfully embody and participate in the missio dei. These monastic and missional movements make up the foundation for the community we have been called to form and are the roots of our particular faith community (NieuCommunities).

I want to take the next few days to explore the history (it will only be brief!) and modern practice of missional-monastic community (some may call this New Monasticism). In the Church today there is a building movement for missional community and a resurgence of interest in the monastics.

What would our faith community’s look like if we were to glean the insights of formation from the monastics, while embracing our vocation of shared mission?

I will begin by taking a brief look at the development of monasticism and its implications on the way we form and live out community today.

The Monastic Stream of Missional-Monastic Community

As a grassroots, Spirit-driven movement, the early Church thrived under the heavy hand of the Roman Empire during the first three hundred years following Jesus’s life and ministry on earth. It was a movement that didn’t offer allegiance to Rome and the “divinely” appointed Caesar, but instead offered allegiance to Jesus. However, as Christianity became more widely accepted (the majority of Roman citizens became “Christians” during the fourth-century-reign of Constantine), Christian nominalism began to pervade the Church. The unique soil that had given birth to a cruciform faith was reduced to a label that required less and less abandon to the self-sacrificing way of Jesus. Christianity became “the thing to do” rather than the high calling of one submitted to the way of the cross.

to Jesus. However, as Christianity became more widely accepted (the majority of Roman citizens became “Christians” during the fourth-century-reign of Constantine), Christian nominalism began to pervade the Church. The unique soil that had given birth to a cruciform faith was reduced to a label that required less and less abandon to the self-sacrificing way of Jesus. Christianity became “the thing to do” rather than the high calling of one submitted to the way of the cross.

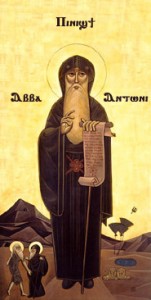

It was this context and ecclesial reality that gave birth to monasticism. Of Egyptian ancestry, Anthony was raised in a wealthy Christian family; after a unique conversion experience, he gave all he had to the poor while choosing to pursue a life of asceticism. Withdrawing from society, Anthony spent the next twenty years of his life in an old fort in the mountains, eating and drinking sparingly as he gave his life to devotion of the contemplative life. For him and for many of his contemporaries, the radical call of Jesus to selfless sacrifice had been lost by the majority the Church, and they saw their intentional way of life as a needed corrective.

Anthony is now known as the Father of Monasticism because his way of life attracted disciples and sparked a new movement that served as a critique to a calcifying Church structure and commitment-less Christianity. Anthony’s fame spread throughout the Empire, and Emperor Constantine and his two sons even took the time and effort to seek out his counsel and prayer.

As the movement developed, it sparked a renewed submission to the radical call of Jesus and took a variety of forms—some much more extreme than others. For example, Simon the Stylite lived on top of a pillar east of Antioch for thirty-six years as he and others like him became known as “athletes of God” through their selfless sacrifice and devotion. In contrast, Pachomus, a fourth-century monastic, thought it best to pursue the monastic life in the context of community and pioneered the development of the monastery. His monastery became so popular that many others were started, and by the end of the fourth century, a developed Pachomian system had been established for the operation of the community.

Along the way, buildings were erected as a way to keep the world away from the cloistered community or monastery. For these monks, the ideal Christian life was not one of direct engagement with the world for the extension of the kingdom, but one of withdrawal out of a desire to be better formed into devoted, self-sacrificing followers of Jesus. Their witness was not through missions or evangelism, but by offering to the rest of the world a countercultural example of devotion.

It was in this context that the monastery became—and largely still remains—primarily an image of spiritual and communal formation rather than missional advancement and engagement. Although there is much more to the early monastic movement, it is this image of the monastery that I want to come back to and build upon for the sake of our conversation.

The monastics intentionally embarked on this way of life with a specific purpose of calling the Church back to its radical vocation to be a community rooted in the way of self sacrifice and obedience to Jesus. Have our churches become monasteries removed from missional engagement as a prophetic presence like the monastics or out of pious isolation? How might we create communities of formation and prophetic presence as a way of advancing our participation in the missio dei?

Tomorrow – Part Two: Missional Stream of Missional-Monastic Community

The majority of this post is an excerpt from my book (with Rob Yackley) Thin Places: Six Postures for Creating and Practicing Missional Community, published by The House Studio

Leave a comment